by Yavuz Baydar

So, this is the end. Well, more or less so if you read into the most recent General Affairs Council statements about the state of accession negotiations between Turkey and the EU.

Following up on the overwhelming European Parliament (EP) vote to freeze the talks, it was the Austrian veto that did it. It meant that, although 27 other member states did not agree with the EP vote, Vienna blocked a joint statement.

Slovakia added that the talks were to remain ‘open-ended’. Turkey was downgraded from negotiating partner to ‘candidate’, and it became clear that no more chapters would be opened.

It means, in plain language, the case of Turkey is now placed into a ‘deep freeze’.

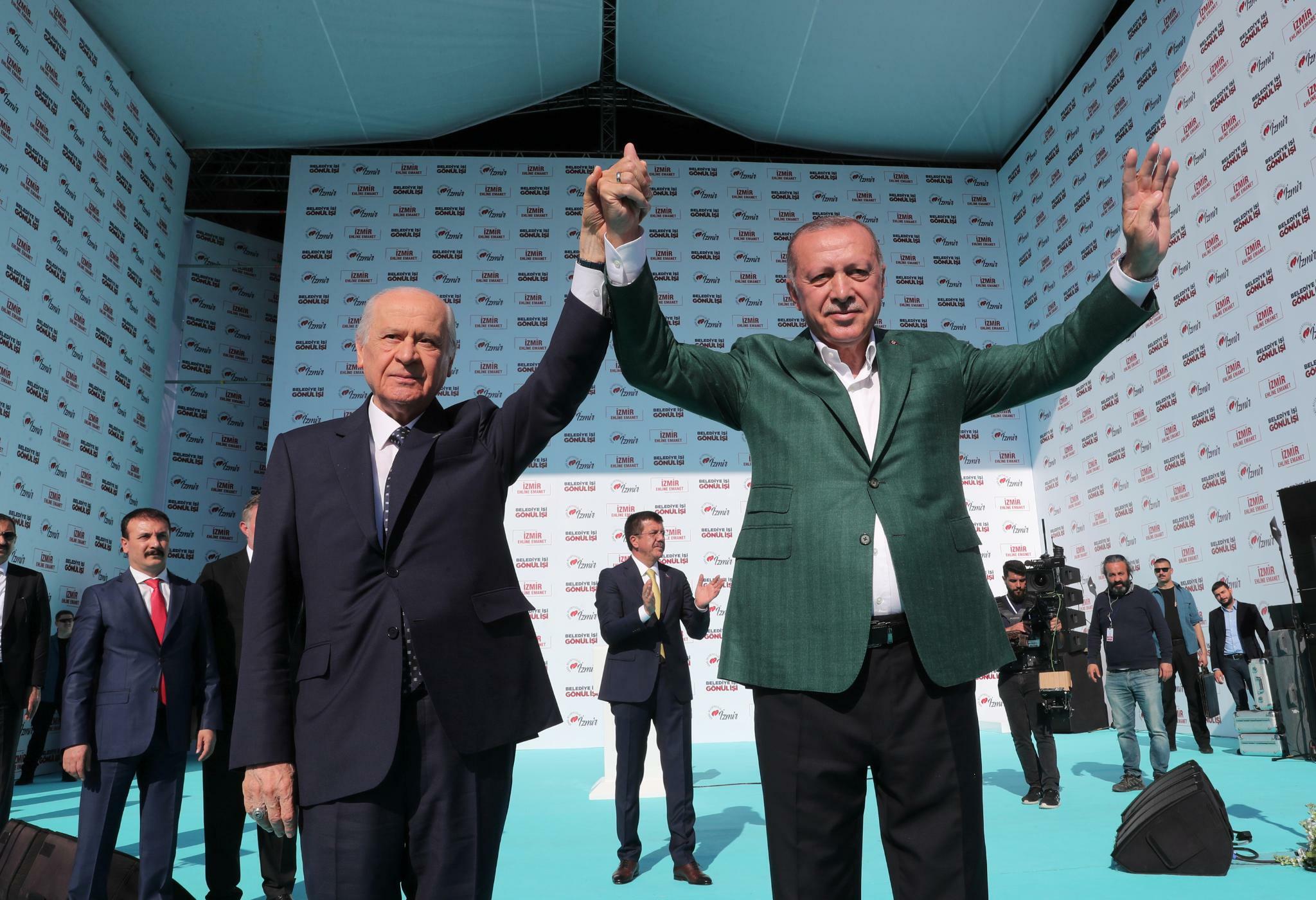

‘The dream is over’ said a colleague over the phone. ‘Unless a miracle happens, namely President Erdoğan and his team somehow, someday suddenly wake up as democrats and hand all the basic rights and freedoms back to Turkish citizens, then we will see the ice, probably melting.’

It was inevitable, this road clash. By and large, all the indicators showed a blitz deterioration in Turkey’s utterly fragile democratic order. The aftershocks of the botched coup, which many agree exposed a clear intention of Erdoğan to speed up his power grab, brought the patience to breaking point. Austrian veto pounded the final nail in the coffin titled, ‘Turkey’s European Perspective’.

Step by step, measure by measure since July 15, Erdoğan in a solo act pushed Turkey farther and farther away from democratic values; closer and closer to the norms that resemble, say, Belarus.

And report by report, we were given a diagnosis of a path wide open to full-scale authoritarianism. On Monday, Venice Commission, an advisory body to the Council of Europe, a panel of top constitutional experts, issued a 47-page long report, concluding that in the massive purge after the failed coup, Turkey violated its own constitution. The details of the report show a state of misery regarding the rights and freedoms.

In a related development, the European Network of Councils for the Judiciary (ENCJ) said last Friday that it could no longer allow Turkish judges and prosecutors represented in its network, stating that the country’s top judicial body, Supreme Board of Judges and Prosecutors (HSYK) was no longer independent from the government.

These are the sign on how rapidly Turkey drifts apart from the European legal system, which it belonged to since early 1950’s. It’s a highly dramatic development.

Add this another report – one of many of its kind. In a fresh statement, New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) let us know that at least a third of all jailed journalists in the world were in Turkey. According to CPJ, 81 journalists were kept behind bars, compared to the global total of 259. But CPJ’s figure was rather modest, as other international organisations claim at least 146 of them are in pre-trial detention. Which means Turkey has more than half of the global number of imprisoned journalists. It is, by any measure a shameful achievement of unprecedented dimension.

Perhaps no more to be said about the state of misery. Indicators on two main pillars of any democracy, judiciary and media, are enough to understand it.

Yet, as Turkey’s European vocation may have the end in sight, the same can not be said about the nightmarish journey it is under the captainship of Erdoğan. The shock of the recent terror attack in Istanbul, which cost at least 45 lives, turned rapidly into a new wave of crackdown, leading to the arrests of more than 500 representatives of the pro-Kurdish HDP party and at least 200 citizens who had expressed critical views in social media. Post-coup mood, tainted by frenzy and witch hunt, took even darker tones, which leaves every citizen in disagreement with Erdoğan and the AKP, scared of ending up in harassment and jail. Day by day, we watch a great country turn up to a full-fledged Republic of Fear.

As to prove Austria right in its veto, Erdoğan’s autocratic push does not show any signs of a slow-down; neither in deed nor in words. In addressing the large crowd of district representatives (who are responsible of administration in city districts and villages) which he developed into a tradition since he became president – he went ballistic about the foreign powers, and claimed that there was a conspiracy to have his administration removed from power – by simply tweeting.

Here is a sample of what he said in that meeting:

‘There is not the slightest reason for any group in my country to justify resorting to terror to seek their rights. You can not even find in European countries our granted right to seek justice here. Freedom, democracy.. these are fairy tales. This level of tolerance is not to be found anywhere else.’

‘I am calling our security forces. Use your power to the full! Those of you who die will be martyrs, but we need our soldiers alive…’

I am calling you district representatives: you have also a duty to find out who is staying in which flat or house at your area. Inform the security forces about all this.’

Our land is in the circle of fire. These times are as important and critical as our Liberation War (1919-1922). It will cause vital consequences.’

‘We will, in the name of our martyrs, break arms and legs of all those who intend to harm our flag. And those who want to overthrow us by tweets and schmeets will be made to pay a high price!’

Those words may be taken lightly, as part of the populistic scheme to whip up the crowds, but as one prominent dissident, Prof Baskın Oran recently told a judge in an ‘insulting the president’ case: ‘(President) is the highest authority of the state. He exerts full influence over the armed forces, the judiciary and large swaths of the people. In such a sense that whatever word comes out of his mouth is regarded as orders.’

There are thousands of examples on Erdoğan’s ‘recommendations’ leading to – generally – further restrictive measures.

It is for this very reason that his loud declaration of a ‘national mobilisation’ on Wednesday that sent chills down the spines. This is not a term used frequently and, as many in Turkish opposition already reacted, it signals further man-hunt and war. Erdoğan used it in the context of fighting against all terrorist organisations, but added that ‘we shall not remain in defence position any longer’, which raises question marks.

Is it a sign for further crackdown against Kurds, Alevis and leftists – who Erdoğan sees as hostile to his power? Is it a call for majoritarian uprising? Or is it just a fear-mongering as part of his plans to cement a life-long presidency?

With the EU perspective in deep freeze and Turkey’s judicial system being alienated from the western mechanisms and in shatters, no independent observer feels sure where the power-grab process in Turkey will end. What the cost and consequences will be, believe me, nobody has any clear idea.

That is the chilling part.

In daily reflexes, I keep returning to dark history of Germany from February 1933 on, reading details in the hope of finding some clarity, clues.

I don’t wonder wonder why.