Open Europe’s Pawel Swidlicki outlines the recent domestic changes the Polish government has introduced to the country’s Constitutional Tribunal and public media which have been described as undemocratic. Pawel argues that while they are a cause for concern, an EU intervention in Polish domestic politics could easily backfire.

What is happening in Poland?

Since it came to power, Law and Justice has wasted little time in introducing sweeping reforms to state institutions which have widely been described as undemocratic both at home and abroad. Two measures are particularly problematic. Firstly, the appointment of five new judges to the Country’s Constitutional Tribunal, an act the Tribunal itself deemed partially unconstitutional. This was followed by package of measures making it very difficult for the Tribunal to rule against any future government legislation – laws can only be blocked by a two-thirds majority of at least 13 out of the 15 judges.

Secondly, a new public media law giving the government direct control over top personnel appointments (and therefore, de facto, a significant degree of control over output). Law and Justice politicians have argued that the public media should act as a “shield” for the national interest, and in the eyes of the party’s most ardent supporters, the national interest and the party’s policy platform are one and the same. The law was rushed through parliament between Christmas and New Year with very little debate and/or scrutiny and has been widely condemned by press freedom groups.

While Law and Justice promised change, the scale and speed has taken many by surprise – in its election campaign the party adopted a more conciliatory tone and placed moderates such as the now Prime Minister Beata Szydło front and centre, while controversial figures such as party leader Jarosław Kaczynski took a backstage role. It had seemed that the party had learned that in order to get back into power, it would have to act with greater restraint; perhaps winning an outright majority emboldened the party to be more radical than it would otherwise have been.

Is the criticism warranted?

Although some of the apocalyptic rhetoric about the threat to Polish democracy has been over the top – Law and Justice supporters are entitled to point out that the previous Civic Platform government did not always assiduously obey the Constitutional Tribunal’s rulings and appointed its own supporters to senior public positions – many of the changes, as well as the manner and speed at which they have been pushed through, are objectively a cause for concern. Essentially, the Law and Justice approach to politicised public institutions is not to depoliticise them, but to ensure they reflect their own ideology and objectives.

It is true that public institutions do not operate in a political vacuum, and even in mature democracies there is often a robust debate about the political positions adopted by public bodies such as quangos, the degree to which the judiciary should be sensitive to public opinion (on issues such as the interpretation of human rights laws for instance) as well as extensive scrutiny of any bias exhibited by public media. However, there needs to be a sense of moderation and fair play – it is simply not healthy for any political party, even if it has an electoral mandate, to remove all checks and balances on its power. Even if one accepts the premise of Law and Justice’s arguments about the need for reform in principle, the best that can be said is that it has been excessively heavy-handed.

The problem is further exacerbated by the party’s confrontational nature which results in all disputes being framed in terms of ‘us vs them’, with people who disagree with its policies depicted as having ulterior or suspect motives, and/or of being disloyal to the national interest. Party leader Jarosław Kaczynski described opponents as the “worse sort of Poles” while Foreign Minister Witold Waszczykowski has portrayed them as “vegetarians and bicycle riders” hostile to traditional Polish values.

It is notable that criticism has not been limited to the likes of The Financial Timeswhich could never be accused of being sympathetic to Law and Justice from the outset, but also The Washington Post which described the reforms to the Constitutional Tribunal as “disturbing”.

What tools does the EU have at its disposal?

Following mounting concern about the slippage of democratic norms in several member states, above all in Hungary under Viktor Orban, in 2014 the EU adopted a new ‘rule of law mechanism’ intended to address “systemic threats to the rule of law” in any member state. This was designed to complement the standard Article 258 procedure for infringements of EU law and the ‘nuclear option’ of Article 7 which, at its most severe, allows for the suspension of voting rights in case of a “serious and persistent breach” of EU values. The latter is highly unlikely to be deployed as it requires 4/5 of member states to agree (in the case of the preventative mechanism) and unanimity (in the case of the sanctions mechanism).

On Sunday, EU Digital Economy Commissioner Günther Oettinger told Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung that “There are many reasons for us to activate the ‘Rule of Law mechanism’ and place Warsaw under surveillance”. If formally invoked, this procedure could have three steps:

- Firstly, the Commission will investigate and assess whether there are “clear indications of a systemic threat to the rule of law”, and if it decides that there are, it will “initiate a dialogue with the member state concerned.”

- Secondly, unless the matter has already been resolved, the Commission will issue a “rule of law recommendation”, essentially giving the member state concerned a specific time limit to address the problems it has identified.

- Finally, if the Commission considers the problem has still not been satisfactorily resolved, it may recommend the invocation of Article 7 as described above.

For now, as we reported on Tuesday, the Commission seems focused on reviewing and discussing the Polish government’s decisions rather than launching any formal investigation linked to the ‘Rule of Law mechanism’. [Update: this may be changing, according to DPA, Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker is considering launching such an investigation, making the next section even more pertinent]

Why the European Commission should tread very carefully

Given that Commission President Juncker has promised a ‘more political Commission’, there may be a temptation to intervene in the Polish dispute, while the European Parliament – which can itself recommend the invocation of Article 7 – is scheduled to hold a debate about the situation in Poland. European Parliament President Martin Schulz has already compared the changes to the Constitutional Tribunal to a “coup”.

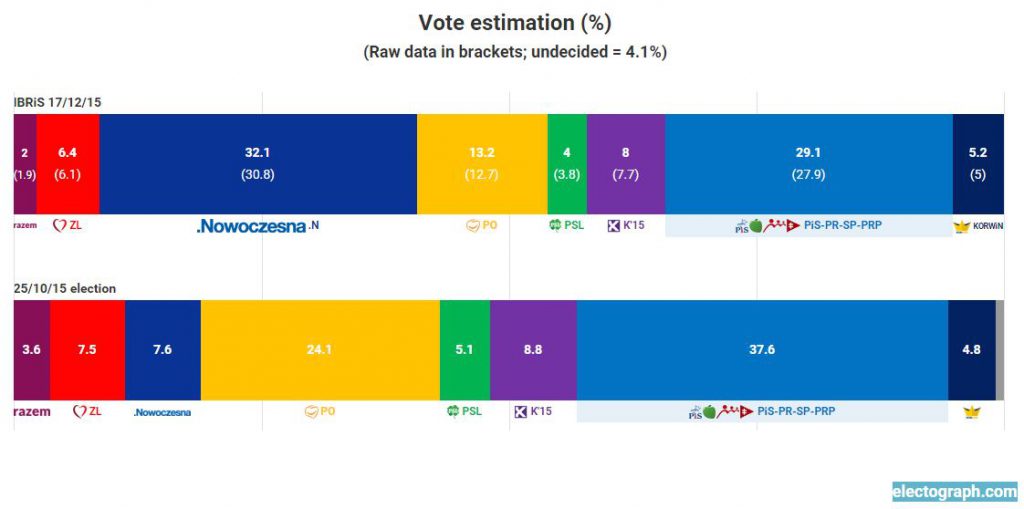

However, the EU should be wary of involving itself in Poland’s domestic politics for a number of reasons. Firstly, there is already a robust, cross-party opposition movement which is challenging the reforms. Law and Justice only won a narrow majority (enabled by the number of votes cast for parties that did not get seats) and its sweeping changes, which it did not explicitly spell out before the election, have already caused its support to plummet in the polls. As the chart below (via electograph) shows Law and Justice and affiliated parties have fallen from 37.6% in the October election to 29.1% in the latest poll. Warsaw is not Budapest where Orban has a thumping parliamentary majority and can unilaterally amend the constitution.

Secondly, a heavy-handed EU intervention could actively undermine the domestic opposition by linking it firmly to ‘foreign’ interests. While many Poles may be sceptical about the reforms, they will not take kindly to being lectured by the likes of Martin Schulz who is widely seen as epitomising Western European arrogance and smugness. As noted above, Law and Justice thrives on confrontation and would try to exploit any such intervention to reinforce their credentials as the defenders of Polish interests – it is often said that Poles are never as united as when under external attack. Waszczykowski has already dismissed European Commission Vice-President Frans Timmermans as “an EU official” and “not a legitimate partner” after he wrote to the Polish government asking for clarifications on the changes to the Constitutional Tribunal.

Even if it does not formally invoke the rule of law mechanism, there is little doubt the Commission will put pressure on Warsaw to reverse its course. Given the extent to which Poland is economically dependent on the EU (much more so than the UK), Law and Justice may decide to make a couple of concessions allowing all sides to save face. Nonetheless, given the number of crises it is already beset with, the EU can ill afford to spark another crisis of legitimacy by a clumsy and potentially self-defeating intervention in the sensitive domestic politics of one of its largest member states.

- This article first appeared on Open Europe.